Ironically, times of stress are when we need to be on top of our game.Healthcare is experiencing a dramatic shift on so many levels: patients are frightened and hesitant to seek care unless they think it is an urgent issue, the world is dealing with a pandemic that has many unanswered questions, and healthcare providers are growing increasingly anxious about their own risk of exposure. To name just a few of the challenges! Of course, while the pandemic represents a crisis of unequal proportions, not all urgent situations are pandemic-related. It just adds to the stress of dealing with non-COVID-19 emergencies. Needless to say, the time is ripe for significant psychological impacts on healthcare providers. Just being aware of this increased risk of the deleterious impact of stress is the first step to improving one’s ability to cope. It is important to be aware that you, your staff and your patients are probably all experiencing heightened levels of stress.

Ironically, it is during emergency and other high-stress situations where we need to be on top of our game in terms of cognitive functioning, decision making and attention, that we are at greatest risk of having our amygdala’s grab more of our focus, and can significantly affect emotional and mental well-being, both in the short-term and over time 1. Not only do emergency situations call for thinking quickly on one’s feet and making timely (and often life or death) decisions, but the ability to be aware of how one is relating to self and to others, is also critical. That requires a degree of self-reflection, a willingness to engage in self-care, an ability to stay focused on the task at hand, and being capable of adapting to quickly changing circumstances–all this while staying tuned in to how one is relating to others so that they can stay focused and engage in effective decision-making and cognitive processing. As physicians, you are often required to step into a leadership role–making your ability to self-regulate, to communicate and to interact with others vital to successful healthcare outcomes. Trending: The best states for physicians in 2020: The 11 worst states There are strategies for developing your ability in all these areas–practicing mindfulness would be at the top of that list. As scientists and healthcare providers dedicated to evidence-based practices, mindfulness deserves a place in your toolkit–but not just for your patients–for you too! Recent meta-analyses point to the many psychological and physical benefits of mindfulness practices for healthcare providers 2,3. So, what exactly do we mean by mindfulness? Perhaps the most widely cited practitioner of science-based mindfulness, Dr. John Kabat-Zinn, gives us this definition: “Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally) 4. What does this mean in practice? It means that we are intentional about where we focus our attention; that we observe what is going on internally and externally) without making an evaluation or judgment (especially about ourselves); and that we stay committed to repeatedly bringing our attention back to the present moment. Why is this a useful practice? Because it has been shown to improve one’s ability to cope when experiencing distress (such as fear, anger, and anxiety), to sharpen one’s focus, and to intentionally direct attention where it is most needed 5. The key to success is simple–practice mindfulness. Like any other skill, the more you practice, the better you get. And if you think you can’t afford the time, think again. Mindfulness can be practiced anywhere and for any period of time. All it requires is an intentional, nonjudgmental focus on the present moment, regardless of what’s going on in that moment. Having an anchor (the most common one being the breath) helps to bring your attention back to the present, over and over again. The more you do this, the better you will get at staying focused and present during any situation. Think of it as a form of stress-training–preparing your mind to focus awareness during a time when it is likely to be most distracted (think crisis or emergency). And like any form of training (be it for a sport, learning a language, or engaging in some form music/art), first you learn the skill and then you practice over and over. There are many resources available for learn mindfulness–such as Kabat-Zinn’s website or any of a number of phone apps. And practicing just 15 minutes throughout the day is enough to make a difference. So, give it a try. You might just find that not only does your mindset and ability to cope at work improving, but other aspects of your life as well. And there is an added benefit–research finds that people who spend more time focused on the present, rather than engaging in mind wandering, are happier. Read More: 5 tips to negotiate favorable payer contracts Ready to practice? Take a quiet moment (the more the better) and focus on your breath, where-ever you notice it in your body. When you find your mind wandering, gently bring it back to the breath. Whenever you find yourself experiencing negative emotions, observe what you are experiencing without judgment, and bring your focus into the here-and-now. It’s that easy. Catherine Hambley, PhD, is CEO of Brain-Based Strategies Consulting, where she specializes in executive coaching, leadership and team development and organizational transformation. Catherine has an extensive background in healthcare, where she works with physicians, nurses and hospital executives to create cultures of learning, collaboration and engagement. Check out her website at www.brainbasedstrategies.com References:1. Harvey, S., Milligan-Saville, J., Paterson, H., Harkness, E., Marsh, A, Dobson, M. & Bryant, R. (2016). The mental health of fire-fighters: An examination of the impact of repeated trauma exposure. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50(7), 649-58. 2. Gilmartin, H., Goyal, A., Hamati, M., Mann, J., Saint, S., & Chopra, V. (2017). Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers–A systemic literature review. The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 130(10), 1219.e1-1219.e17. 3. Westphal, M., Bingisser, M., Feng, T., Wall, M., Blakley, E., Bingisser, R., & Kleim, B. (2015). Protective benefits of mindfulness in emergency room personnel. Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 175, 1: pp. 79-85. 4. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994), Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion. 5. Zanesco, A., Denkova, E., Rogders, S., MacNulty, W. & Jha, A. (2019). Mindfulness training as cognitive training in high-demand cohorts: An initial study in elite military servicemembers. Progress in Brain Research, 244, 323-354. Effective teamwork leads to fewer medical errors and better patient care.Medicine is a team sport-the collective is often much greater than the individual when it comes to patient care, innovative ideas, productivity, and efficiencies. Even more important is that effective teamwork leads to fewer medical errors.1

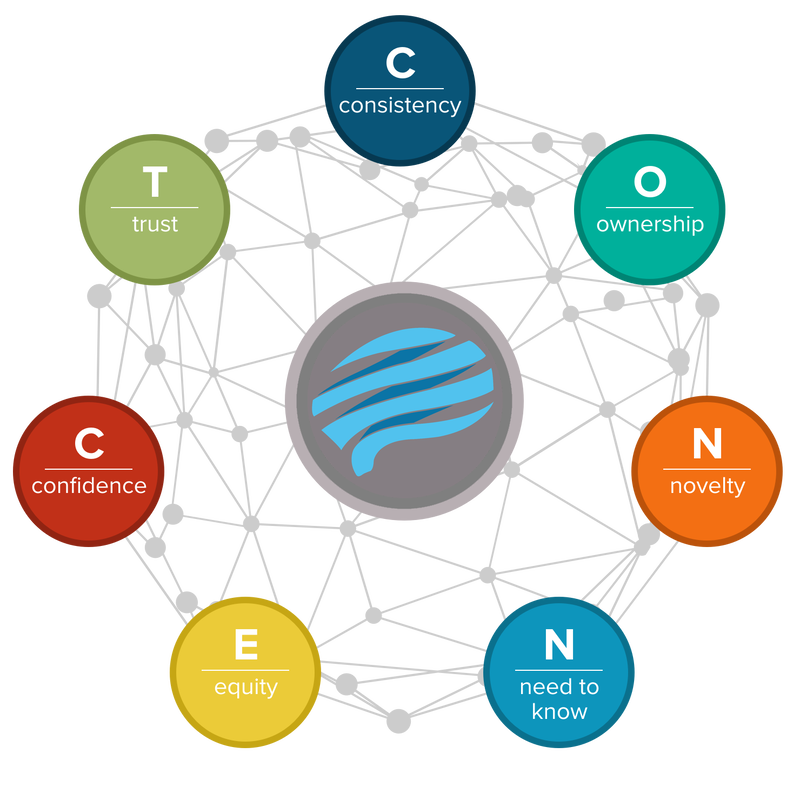

It’s helpful to think about team tasks rather than individual ones because within a team there exists a diversity of skills, experience, talent, and perspective, allowing members to take on more complex and involved work than individuals. The science of teamwork has made significant advances, such that we can now draw upon evidence-based practices to guide us in forming and maintaining higher function teams.2 Teams come together for a variety of purposes, for different time spans, and with differing skills sets and background. Some teams are highly interdependent (they need each other to accomplish tasks), while others work together more independently, seeking advice or guidance from team members when needed. For example, in physician practices, you are likely to have highly interdependent teams-such as the team focused on direct patient care and one that is focused on administrative responsibilities. Depending on the size and complexity of the practice, one team may be focused on both “front” and “back” office responsibilities. Trending: The effects of nurse practitioners replacing physicians Despite the differences in team purpose, composition, structure, and inter-relatedness, there are several factors common to all teams. The most important one being a concept of “psychological safety”- where team members believe that it is “safe” to share their thoughts, ideas, and experiences (even mistakes) without fear of judgment or retribution.3 Bearing in mind that not all teams are created equal, below are some strategies worth considering to get the most from your team. 1. Develop a team mission – your purpose for being. When people all agree on a common purpose and feel that they are all working towards that purpose, there is a greater sense of camaraderie and teamwork. Reminding people of that common purpose (i.e. patient care and comfort) helps them feel a sense of meaning and significance and helps break down and/or avoid silos. It is critical for teams to understand that success is best defined by achieving your purpose In other words, it is more about team success than individual success. 2. Develop team agreements. One of the most common traits of successful teams, is that they have established norms by which they agree to operate under.4 Here are some questions I typically use when helping teams develop their agreements: a. What are the behaviors we need from each other to develop greater trust? b. How do we want to make team decisions? c. How do we ensure that everyone’s voice is heard? d. When we have an issue to address with one of our team members, are we willing to go directly to the person (and not talk behind their backs). This last one is critical. I often help teams learn how to have difficult conversations in an effective and productive way. Team members need to not participate in talking about others and instead, encourage their colleagues to go directly to each other. 3.Clarify team roles (what is expected of each other individually and of the team collectively) and create team goals. When team members clearly understand each other’s roles and responsibilities, they can then find opportunities to help each other out. I often ask healthcare teams how they define success at the end of their day. My objective is for them to see that their work is all about the best interest of patient care, and that includes helping out our colleagues when needed. Establishing a common set of metrics helps to define success and ensure that the team is able to measure their progress. The ability to achieve goals not only boosts team morale and reinforces the team mission, it also helps the team to identify factors that contributed to their success. When goals are not achieved, it allows the team to discuss strategies that might be more effective. Read More: Take back control of uncompensated time 4. Learn from mistakes and failures. Teams that learn together, bond together. It is critical, especially in a health-care setting, that mistakes are seen as an opportunity to learn and improve, versus an opportunity to shame and blame. The team agreements should address this issue. You want people to openly discuss errors and near misses so that they can continually improve patient care and safety. A culture of continuous improvement among a team means that everyone knows that mistakes are bound to happen and that the best thing that can come from them is learning. 5. Provide opportunities for the team to get to know each other on a more personal level. One great way to do this is through a personality workshop (see my previous article on the NeuroColor personality assessment). It is a perfect opportunity to learn about people’s different styles, preferences, communication behaviors, and ways they might be misunderstood. It can lay the foundation for ongoing sharing, a key element for teams to develop psychological safety. Catherine Hambley, PhD, is CEO of Brain-Based Strategies Consulting, where she specializes in executive coaching, leadership and team development and organizational transformation. Catherine has an extensive background in healthcare, where she works with physicians, nurses and hospital executives to create cultures of learning, collaboration and engagement. Check out her website at www.brainbasedstrategies.com References:Edmondson, A. The kinds of teams health care needs. Harvard Business Review, December 16, 2015. Salas, E., Reyes, D. and McDaniel, S. The science of teamwork: progress, reflections, and the road ahead., The American Psychologist, 2018, Vol. 73, No. 4, 593-600. Edmondson, A and Zhike, L.. Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014, Vol. 1: 23-43 Duhigg, Charles. What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times Magazine, Feb. 25, 2016.

Catherine Hambley, PhD, is a consulting psychologist who offers brain-based strategies to organizations, leaders, and teams to improve their effectiveness and promote greater success. She can be reached at [email protected]. Archives May 2020 Why should you learn about the brain?Here are 3 main reasons:

Here is what you need to know to start translating neuroscience into practical skills and behaviors.

Catherine Hambley, PhD, is a consulting psychologist who offers brain-based strategies to organizations, leaders and teams to improve their effectiveness and promote greater success. She can be reached at [email protected].

You can facilitate positive, meaningful change for yourself through a few simple steps. I encourage you to direct your attention to solutions, versus an over-focus on the problem. There is a scientific basis to this approach – the more we focus on a problem, the more we can move into an emotional state that makes us feel threatened in some way. For example, when we focus on a problem, we might feel incompetent, disliked, or unimportant. These feelings cause the limbic system to become activated, making it difficult to develop insights, which is key to creating lasting change. Try it out right now. Consider an area of your life where you would like to create change. An example of a dilemma would be that you want to spend more time with family, but you can't get your work done in a reasonable period of time. I am going to ask you some questions that might allow you to develop insight into your own thinking. You can use this insight to identify what you might do differently to address the problem or challenge. These questions are useful for you to consider anytime you are faced with a dilemma which you do not know how to best resolve. You will notice that the questions do not go into the details of the situation, but rather have you focus on your thinking. By directing attention to your thinking, you are more likely to develop useful insights. Please write your answers down or discuss them with someone who can help you clarify your thinking. Insight-Creating Questions How long have you been thinking about the situation? What impact does this thinking have on you? How often do you think about it (how many times a day)? How clear has your thinking been? How important is this issue to you (on a scale of 1 to 10)? What priority have you given it (on a scale of 1 to 10)? What priority do you think you should give it? How would it feel to have this issue resolved? How satisfied are you with the amount of thought you have given to the situation? How committed are you to resolving the dilemma? What insights are you having now about the situation? What do you now notice about your thinking? What are one or two things you will do differently now that you have thought about this? Based upon the insights you have developed as a result of addressing these questions,begin to identify specific action steps that you would like to take to move from insight to action. Catherine Hambley, PhD, is a consulting psychologist who offers brain-based strategies to organizations, leaders and teams to improve their effectiveness and promote greater success. She can be reached at [email protected].

Do you want some simple strategies to encourage others to learn — both from their successes and their mistakes? Would you like to help people arrive at their own solutions? Do you avoid giving "constructive feedback" because it rarely goes well? Easy-to-learn communication skills will help others build upon their strengths and discover ways to improve. Here are a few strategies to employ: 1. Use the right words: If you want to help others get into a learning mode (what is referred to as a growth mindset), the language you use really matters. Avoid words like always, never, only, can't and instead, use words like learn, grow, develop, try out, and progress. The former set of words triggers the brain into a fixed mindset — a belief that one cannot change. If people believe they are really good at some things and not good at others, they are not primed for learning. In contrast, when people believe that there is room to learn and grow, their brain in in a growth mindset. 2. Leverage mistakes: It may seem oxymoronic, but often the only path to learning is through trial and error. Avoid thinking about mistakes or mishaps as failures – instead, think about them as learning opportunities. We all have witnessed babies learning to walk. What do they do? They walk then fall then walk then fall…. And their parents cheer them on. Because we know that is how they learn and develop. So the next time someone makes a mistake (including you), ask them (or yourself), what can I learn from this experience? Contrast this to getting overly critical, blaming, or angry – which does little to foster a learning environment. 3. Always start a difficult conversation by stating your intention: Prior to giving any feedback, be clear on your intention and communicate it to the person. If your intention is not positive, I suggest you do not give feedback because negative intentions are easily detected. 4. Always give feedback that helps others improve: Practice using this communication model — SBI-I (situation, behavior, impact, and inquiry) and you will find that giving constructive input is much easier than you thought. Here is how to transform one of those difficult conversations into a learning conversation. Let's use an example: Your medical assistant gave a patient incorrect information about their health situation.

Practicing the SBI-I communication model will allow you to gain skill and confidence in managing difficult situations with your staff (and anyone else in your life where these conversations may arise). Avoid blaming, evaluating or judging and use open-ended questions to help the person arrive at a solution or lesson learned. You can use SBI-I to provide positive feedback as well — when you give someone specific and genuine acknowledgment of what he/she has done well, it becomes a signal to the brain to do more of that behavior. Catch people being or doing good and aim to give at least five positives to every negative. This will help to ensure that when you give constructive feedback, the person is more open to hearing it (it does not feel like one more criticism because you have given lots of positive recognition). This is how you create a learning environment where employees thrive and your practice improves. Catherine Hambley, PhD, is a consulting psychologist who offers brain-based strategies to organizations, leaders and teams to improve their effectiveness and promote greater success. She can be reached at [email protected].

|